日本語-Englishー台灣華語

レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチ「腕・肩・首の筋肉を描いた手稿」

僅かに残された絵画を見れば、レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチが抜きん出た画家でたったことは一目瞭然である。しかしレオナルドがレオナルドたる所以は、残された膨大な手稿にこそある。レオナルドは言っている。「凡庸な画家は絵画に学び、優れた画家は自然に学ぶ」と。レオナルドにとって自然界を写し取ることは美の本質をつかみとることに他ならない。手稿はそれを証明している。

私は1995年に東京都庭園美術館で開催された「人体解剖図展」でレオナルドの手稿をはじめて見た。レオナルドの絵画は観るたびにどこか近づきがたい違和感を抱くのだが、手稿にはレオナルドが直に語りかけてくる率直さがあった。私はその感動を胸に秘め、人体解剖図の中でもとりわけ心に残る「腕・肩・首の筋肉を描いた手稿」を模写することにする。レオナルドの手稿はその生涯にわたって彼が書き綴ったノートである。手稿の大半は失われてしまったが、五千ページが現存している。美術は言うに及ばず、医学、天文学、工学などあらゆる分野に及ぶ。レオナルドの手稿は遺言により愛弟子フランチェスコ・メルツィに託された。メルツィは手稿を整理して出版しようと試みるが、膨大な量とレオナルド独特の鏡文字に苦しみ、存命中には出版することはできなかった。メルツィは手稿を聖遺物のように崇め大切に保管していたが、彼の子孫はその価値を理解せず、膨大な手稿は各地に散逸してしまう。

レオナルドの手稿を初めて意図的に集めたのは、ミケランジェロの弟子レオーニである。レオーニは蒐集したレオナルドの素描や手稿を「レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチの素描集」と「レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチの機械工学に関する素描集」という2冊に分類した。主に芸術的なデッサンを集めた前者が後のウィンザー手稿である。英国にあるレオナルドの手稿は何れもレオーニから出たものである。英国のウィンザー城王立図書館が所蔵する解剖手稿は、1485年から1515年の間に綴られたものである。

レオナルドはヴェロッキオの徒弟時代から解剖学の知識習得に努め、芸術家の領分をはるかに超えた多くの人体解剖を行っている。レオナルドは1510年から1511年にかけてパドヴァ大学解剖学教授のマルカントニオ・デラ・トッレとともに共同研究を行っている。この「腕・肩・首の筋肉を描いた手稿」は、丁度その頃に記述された手稿である。 レオナルドの人体解剖に関する記載は、骨格はもちろんのこと、そこに張り巡らされる筋肉・血管・神経の精密な描写から始まり、さらにその機能、機械への応用と関心が進んでいく。

ルネサンス期には古代ギリシャ時代の自然思想を継承し、宇宙全体をマクロコスモスと呼び、人間はミクロコスモス(小宇宙)と呼ばれた。それら二つのコスモスは呼応しているという思想がレオナルドにも影響している。 レオナルドは人間の枠組みたる骨格と、大地の支柱たる岩石を比較する。大洋が潮汐によって膨張・収縮するように、人間の肺は呼吸により膨張・収縮を繰り返す。人間の体内に血管が分岐しているとすれば、大地にも縦横に水脈がめぐっているはずだ。こうしてとめどなく疑問と探求の連鎖にのめり込んで行く。 もしレオナルドが解剖学に関する研究を本にまとめていたならば、世界初の本格的な解剖医学書となったはずだ。

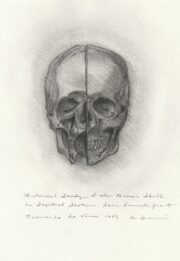

レオナルドの手稿は、解剖学に関する僅かなものだけが1632年にフランスで出版され、絵画に関する手稿が1651年に「絵画論」として出版されたのみで、次第に世間から忘れ去られてしまう。しかし科学技術が大きく進展した19世紀になって、レオナルドの先駆的な研究は再び注目を集めるようになる。 ウィンザー手稿の「腕・肩・首の筋肉を描いた素描」はペンで描かれている。心地よいスピードで線が引かれ、素描の合間に鏡文字でメモが書き加えられ、思いついたようにアイデアが書き留められている。それでいて全体に独特の美しさを醸し出している。解剖をやったことのない私にははじめからペンで描くのは難しい。まずは修正の効く鉛筆で描くことにする。

ウィンザー手稿の「腕・肩・首の筋肉を描いた素描」は正面から側面に至る4つの角度から描かれている。どちらから描いたのかがとても気になる。左利きのレオナルドはインクが手に付かないように右から描いたのだろうが、私は馴染みのある正面向きから描くことにする。右から二番目の解剖図が最も力を入れて描いているように思える。この角度はレオナルドが肖像画を描くときの姿勢だからか、解剖図なのに生きているように感じられる。左側の解剖図になるにつれて、次第に左上がりとなる。それが心地よいリズムを生み出している。腕はまるで真理を指し示すかのように中心に向かって伸びている。この腕の解剖図では、頭蓋骨の解剖図のように斜線による繊細な陰影は付けられていない。その代わり筋肉の緻密な描写が陰影の役割を果たし、筋繊維の細かな描写が斜線にとってかわって美しい。 レオナルドは解剖図でさえも気品があって美しい。

私はレオナルドの解剖図を描きながら思う。レオナルドが他の画家と一線を画して独特の魅力を放っているのは、表層的な絵画ではなく、神秘を内包しているからなのだ。レオナルドは神秘を神秘として崇めるのではなく、純粋に科学的にとらえなおし、それでもたどり着けないものこそが神秘なのだと理解していた。レオナルドの絵にはそれが描き込まれている。レオナルドにあって他の画家にないもの、それは神秘を極めた品格である。

Skull’s Anatomical Manuscript

頭骨的解剖手稿

Anatomical studies

Just by looking at the few remaining paintings, it is immediately apparent that Leonardo da Vinci was an exceptional artist. However, what truly defines Leonardo as Leonardo lies in the vast collection of manuscripts he left behind. Leonardo himself said, “Mediocre painters learn from painting, great painters learn from nature.” For Leonardo, capturing the natural world was nothing less than grasping the essence of beauty. His manuscripts prove this. I first saw Leonardo’s manuscripts at the “Exhibition of Anatomical Drawings” held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum in 1995. While Leonardo’s paintings always evoke a certain unapproachable discomfort upon viewing, his manuscripts conveyed a directness as if Leonardo himself was speaking directly to the viewer. I was deeply moved by this and decided to replicate the manuscript that particularly resonated with me, depicting the muscles of the arm, shoulder, and neck.

Leonardo’s manuscripts are notes he compiled throughout his life. Although most have been lost, five thousand pages still exist today, covering not just art but medicine, astronomy, engineering, and more. By Leonardo’s will, these manuscripts were entrusted to his beloved pupil Francesco Melzi, who attempted to organize and publish them. However, Melzi struggled with the sheer volume and Leonardo’s unique use of mirror writing, and was unable to publish them during his lifetime. Melzi treasured the manuscripts like relics but his descendants, not understanding their value, allowed them to scatter far and wide. The first deliberate collection of Leonardo’s manuscripts was by Michelangelo’s pupil, Pompeo Leoni, who divided the collected sketches and manuscripts into two volumes: “Drawings by Leonardo da Vinci” and “Mechanical Engineering Drawings by Leonardo da Vinci.” The former, mainly consisting of artistic drawings, became known as the Windsor Manuscripts. All of Leonardo’s manuscripts in England came from Leoni. The anatomical manuscripts housed in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle were written between 1485 and 1515. Leonardo, from his apprenticeship under Verrocchio, pursued knowledge of anatomy far beyond the domain of artists, conducting numerous dissections. Between 1510 and 1511, he collaborated on anatomical studies with Marcantonio della Torre, a professor of anatomy at the University of Padua. The manuscript depicting the muscles of the arm, shoulder, and neck was written around this time.

Leonardo’s anatomical records start with precise depictions of the skeleton, muscles, veins, and nerves, and advance to their functions and applications in mechanics. During the Renaissance, the ancient Greek idea of the cosmos as a macrocosm, with humans as a microcosm, influenced Leonardo. He compared the human skeletal framework to the support structure of the earth, the expansion and contraction of the oceans with the tides to the breathing of human lungs, and suggested that if veins branched throughout the human body, then waterways must similarly traverse the earth. Engaging endlessly in this chain of questions and explorations, if Leonardo had compiled his anatomical studies into a book, it would have been the world’s first comprehensive text on anatomy. Only a fraction of his anatomical work was published in France in 1632, and some of his writings on painting were published in 1651 as “A Treatise on Painting,” eventually fading from public memory. However, with the advancement of science and technology in the 19th century, Leonardo’s pioneering research began to attract attention once again.

The “Sketch of the Muscles of the Arm, Shoulder, and Neck” in the Windsor Manuscripts is drawn in pen, with lines drawn at a comfortable speed, mirror-written notes added between sketches, and ideas jotted down as they occurred, all while exuding a unique beauty. As someone who has never dissected, starting with pen was difficult for me, so I chose to begin with pencil, which allows for corrections. The sketches in the Windsor Manuscripts are drawn from four different angles, from the front to the side, and I was curious about which angle Leonardo started from. Being left-handed, Leonardo might have drawn from right to left to avoid smudging the ink, but I decided to start from the familiar frontal view. The second diagram from the right seemed to be drawn with the most effort; perhaps this angle, resembling the posture Leonardo used when painting portraits, made the anatomical figure feel alive. Moving to the left, the diagrams gradually ascend, creating a pleasing rhythm. The arms stretch toward the center as if pointing to the truth. Unlike the skull diagrams, which are delicately shaded with hatching, the arm diagrams use detailed depictions of muscles to serve the role of shading, with the fine portrayal of muscle fibers taking the place of slanted lines to create beauty.

Even in his anatomical drawings, Leonardo managed to imbue them with a sense of nobility and beauty. As I draw Leonardo’s anatomical figures, I realize what sets him apart from other artists is not just superficial painting but the mysteries contained within. Leonardo did not worship mystery as sacred but sought to understand it purely scientifically, recognizing that what remains beyond our grasp is truly mysterious. This understanding is woven into his paintings. What Leonardo possesses that other artists lack is a dignity that has mastered mystery.

李奧納多・達文西「人體解剖圖」(手臂、肩膀和頸部的肌肉手稿)

僅見於留存下來的畫作,就能一眼看出,達文西是一位卓越的畫家。然而,真正讓達文西成為達文西的,是他留下來的大量手稿。達文西曾說:「平庸的畫家向畫作學習,優秀的畫家向自然學習。」對達文西來說,描繪自然界就是抓住美的本質。手稿證明了這一點。我在1995年於東京都庭園美術館舉辦的「人體解剖圖展」中,首次見到達文西的手稿。每次觀看達文西的畫作,總是會感到一種難以接近的不適感,但在手稿中,我感受到了達文西直接對話的坦率。我把這份感動藏在心中,決定臨摹我心中留下深刻印象的「手臂、肩膀和頸部的肌肉手稿」。

達文西的手稿是他一生中紀錄的筆記。雖然大部分手稿已經遺失,但仍有五千頁保存下來。不僅是藝術,還包括醫學、天文學、工程學等各個領域。達文西的手稿由他的愛徒弗蘭切斯科・梅爾齊繼承,他試圖整理並出版這些手稿,但由於數量龐大和達文西特有的鏡像文字,他生前未能出版。梅爾齊像珍視聖物一樣保管這些手稿,但他的後代未能理解其價值,導致大量手稿散佈各地。第一個有意收集達文西手稿的是米開朗基羅的學生雷歐尼。他將收集到的達文西素描和手稿分為「達文西素描集」和「達文西機械工程素描集」兩本。主要收集藝術素描的前者,後來成為了溫莎手稿。英國所藏的達文西手稿都是來自雷歐尼。英國溫莎城堡皇家圖書館收藏的解剖手稿,是在1485年到1515年間編寫的。達文西從在維羅基奧的學徒時期開始就努力學習解剖學知識,進行了許多遠超藝術家領域的人體解剖。達文西在1510年到1511年期間,與帕多瓦大學解剖學教授馬爾坎托尼奧・德拉・托雷進行了合作研究。這份「手臂、肩膀和頸部的肌肉手稿」正是在那時期記錄的。

達文西關於人體解剖的記載,不僅包括骨骼,還有肌肉、血管、神經的精細描繪,進一步探討它們的功能和對機械的應用。在文藝復興時期,達文西承襲了古希臘的自然觀念,將宇宙稱為宏觀世界,人類被稱為微觀世界。這兩個世界相互呼應的思想也影響了達文西。達文西將人類的骨骼架構與大地的岩石支柱相比較,就像大海因潮汐而膨脹和收縮一樣,人類的肺部也會隨呼吸膨脹和收縮。如果人體內有血管分支,那麼大地上也應該有水脈縱橫。達文西不斷地提出問題,深入探索。

如果達文西將他的解剖學研究整理成書,那將是世界上第一本正式的解剖醫學書。達文西的手稿中,關於解剖學的僅有一小部分在1632年於法國出版,而關於繪畫的手稿則在1651年以「繪畫論」出版,但隨著時間漸漸被世人遺忘。然而,隨著19世紀科學技術的巨大進步,達文西的先驅性研究再次引起人們的關注。

溫莎手稿中的「手臂、肩膀和頸部的肌肉素描」是用筆畫的。線條流暢,素描間隙用鏡像文字添加了註釋,似乎隨意記下了想法,但整體散發出獨特的美感。對於我這個從未進行過解剖的人來說,直接用筆畫是困難的,我決定先用可修改的鉛筆畫。溫莎手稿的「手臂、肩膀和頸部的肌肉素描」從正面到側面共有四個角度。我特別好奇它是從哪個角度畫的。達文西是左撇子,可能是從右邊畫起,以免墨水沾到手上,但我習慣從正面畫起。從右邊第二個解剖圖看起來是最用力畫的,這個角度或許是因為達文西畫肖像時的姿勢,使得這幅解剖圖看起來像是活著的。向左側的解剖圖逐漸變為上揚,營造出舒適的節奏。手臂似乎指向了真理的中心。這幅手臂的解剖圖,不像頭蓋骨的解剖圖那樣有斜線的細膩陰影,而是用肌肉的精細描繪來代替陰影,細小的肌纖維描繪取代了斜線,營造出美感。

即使是解剖圖,達文西的作品也具有高貴和美感。畫著達文西的解剖圖時,我思考著,達文西之所以與其他畫家不同,散發出獨特魅力,是因為他的作品不僅僅是表層的繪畫,而是包含了神秘。達文西不是將神秘視為神秘而崇拜,而是純粹地從科學的角度重新理解,認識到還未達到的才是真正的神秘。達文西的畫作就描繪了這一點。達文西與其他畫家不同的地方,在於他探尋神秘的高尚品格。